Some people apologize for reading audiobooks. “I read that!” they’ll say if someone brings up a book they liked, but then catch themselves: “Well, I didn’t really read it—I listened to the audiobook.”

Blindness has cured me of this affectation. I now know that reading happens in the brain, and whether a text enters the mind through the eyes, the ears, or even the fingers, it’s still reading. When I wrote my book proposal in 2019, I still read print. By the time I went into the studio to record the audiobook in spring 2023, I had retired from hard-copy books. I now use a screen reader—a piece of software that can read any digital text aloud in a synthetic voice—to read nearly everything.

But the reality of my life as a narrator (of podcasts, audiobooks, or bed-time stories for my kid) was that in order for me to sound fluent and fluid, I still needed to read visually. My braille skills are such that reading aloud I resemble a kindergartener, sounding out tough polysyllabic lines. My friend M. Leona Godin, author of the wonderful There Plant Eyes: A Personal and Cultural History of Blindness, lost the ability to read visually years ago, but was still working on her braille fluency when it was time for her to record her audiobook. She narrated using what she called “the Cyrano method”: just as in the French play, where Cyrano whispers lines to his friend, who then speaks them to his paramour, Leona listened to her screen-reader going through her text sentence by sentence in an earbud as she read the same sentences aloud. I considered taking this approach, but it sounded very difficult. If I can control the size and contrast of the text, I reasoned, it was worth a shot to try performing it visually.

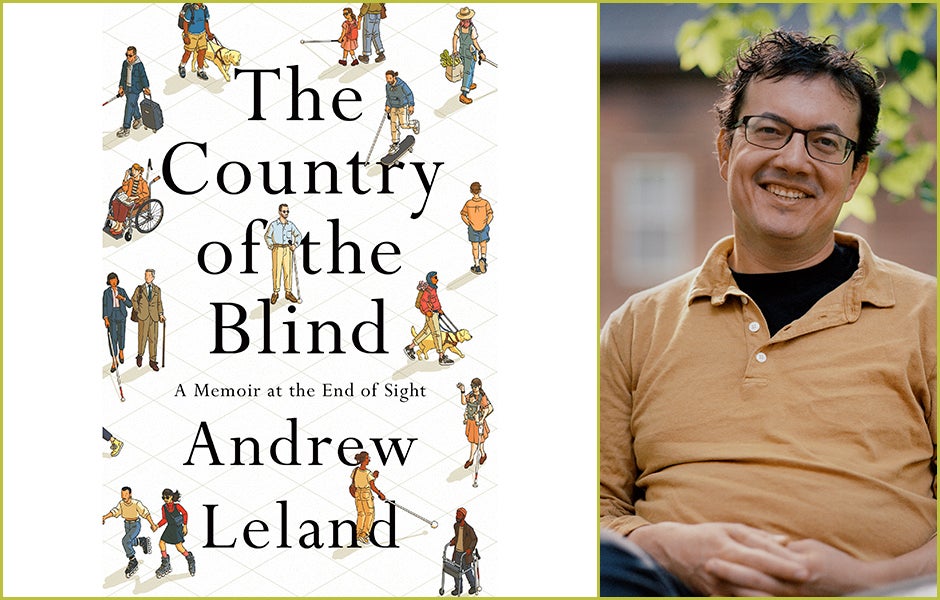

Around the time I was set to record The Country of the Blind, I learned about a typeface called Atkinson Hyperlegible designed by the Braille Institute in Los Angeles, that was developed for low-vision readers like me. It distinguishes each character from the next more than the average typeface does, reducing the possibility of misreading. I converted the final typeset manuscript PDF my publisher sent me into a version I could comfortably read, in 30-pt Atkinson Hyperlegible. I loaded this PDF onto my laptop, which I threw into my backpack and carried from my father-in-law’s apartment uptown to CDM Studios.

On my first day of recording, as I began reading the book, the engineer politely informed me that her super powerful microphone was picking up the sound of my scrolling. This was alarming news: in 30-point type, my laptop screen could barely fit a single sentence—I had to scroll constantly in order to fluidly read more than one clause aloud at a time. “Try pausing and scrolling during the pauses,” she told me. But wouldn’t this sound horribly fractious? “We can cut out the pauses!” she cheerfully replied, assuring me that my experience as a podcast producer was resulting in a fluid read that they could easily edit.

I chose to believe her, plowing forward, silently editing out the pauses in my head to gauge if each thought sounded connected. “I’m going blind as I write this. [scroll scroll scroll] It’s less dramatic than it sounds. [scroll scroll].” After lunch, she played back what it sounded like edited together. Not bad!

With this hiccup sorted, I was able to relax a little and enjoy the process. When I got to the chapter on blindness and reading, I could tell the engineers were enjoying themselves: the first audiobooks were produced for the blind, and it was a deliciously meta moment as we all studied the ways that blindness is interwoven into the history of the audiobook as we produced an audiobook about blindness. That chapter begins with a description of James Joyce’s experiences with visual impairment, and the way that his temporary blindness affected his literary style. Along the way, I quote a 100-letter word from Finnegans Wake: bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk!

I’d failed to contemplate how difficult this word would be to read aloud, and I suggested to the engineers that we might just sample the version I’d heard, as read by the Irish writer Patrick Healy who recorded the novel in its entirety for the first time in 1992. “I can say with almost 100 percent certainty that you won’t get the rights,” Alan, the director, told me. “OK, let’s try it,” I said. I copy and pasted the word into a new document, and blew the typeface up as big as it would go. The word filled the entire screen, and I took my oversized cursor and ran it across each letter, like the bouncing ball in video singalongs. After a few takes, I got it.

There were moments where I felt like a fraud visually reading my book about becoming blind. I asked myself a question I’d asked many times before: am I blind enough to have written this book? But as I read aloud, I was reminded of how deeply the book explores that very question. In that moment, I felt as though I’d written the book to mollify myself about this precise anxiety. It reminded me of an interview I’d conducted, asking a prominent blind researcher a question about adapting to blindness: “I suggest you read your own book,” he advised me.

On my last day of recording, wildfires in Canada plunged New York’s air quality to the worst in the world. When we emerged from the studio for lunch, the sky had turned a muddy orange. I was glad I was nearly done recording; I felt a deep ache in my chest from inhaling so much particulate on my walk to the studio. Even in the climate-controlled, well-insulated studio, it smelled like an old campfire.

I didn’t expect to become so emotional, but as I approached the book’s final pages, I had to pause a few times to let myself cry. I felt momentarily embarrassed, but the engineers were sensitive, clearly used to it. Alan, the director, told me that he had a writer who became so upset recording their narration that at one point they simply announced, “I’m done,” and went home, despite the studio hours that were still booked for the day. I promised I wouldn’t do that—by that point, we’d made it to the book’s last paragraph. I wasn’t sure if it was the personal material I was reading, or that the years of work—reporting, researching, but also thinking and feeling—were all culminating with this moment, or that this might be the last book of mine I’m able to narrate, at least visually. I forced myself to take some deep breaths, knowing that the long silences as I pulled myself together would be edited out later.

I’d been anxious about eye fatigue, which I experience far more readily these days, but during the recording my eyes didn’t bother me much. I think I put so much energy into getting through each day of recording that I didn’t notice the strain I felt until the end of the day, when I could let go. As I walked back downtown to my in-laws’ apartment, I finally allowed my eyes to relax, and they more or less collapsed. Midtown appeared as though reflected in an opaque windowpane, a glare-zapped swirl of traffic and faces. I relied on my white cane a lot. My eyes felt like two pipe bowls whose contents had been smoked down to ashes.

Andrew Leland’s writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, McSweeney’s Quarterly, and The San Francisco Chronicle, among other outlets. From 2013-2019, he hosted and produced The Organist, an arts and culture podcast, for KCRW; he has also produced pieces for Radiolab and 99 Percent Invisible. He has been an editor at The Believer since 2003.